Canonisation as Parody: Reflections on Umberto Eco's Misreadings

- Luisa Ripoll-Alberola

- Blog

- November 12, 2025

PhD life has a way of sneaking up on you. I didn’t expect that the concepts I’m wrestling with in my research would start reshaping how I see everything - from ancient fragments to bookshop browsing. But that’s exactly what happened when I thrifted a second-hand copy of Umberto Eco’s Misreadings at Orinoco Books in Leipzig (a wonderful international bookshop I frequent for its English and Spanish titles).

Published in Italian under the title Diario minimo (1963), the book collects the articles of the eponymous column that Eco held in the literary magazine Il Verri between 1959 and 1961. One would expect, from a literary magazine, weighty reflections about life and death. On the contrary, Eco’s column serves up something far more subversive. Every article builds upon humour, the kind of humour I like to call “humour of literary critics” - highly intertextual, intelligent puns.

Fragments and False Reconstructions

I would like to highlight a couple of the pieces of this collection, as pretexts to reflect on canonisation and culture. In “Fragments”, a future civilisation tries to understand today’s culture from scattered texts. The provenance of these texts is equalised through their fragmentary nature, but they could not be more different: lyrics of Italo-pop songs mixed with verses by Gabriele D’Annunzio. The imaginary scholars fill gaps with plausible but fundamentally wrong hypotheses, creating interpretations that, as readers, we recognise are missing the point entirely.

This is a recurrent source of fun in Eco’s essays - the flawed process of transmission of texts. Another article follows similar premises, “Industry and Sexual Repression in a Po Valley Society”, where confusion reaches such heights that the scholar understands that, in contemporary Italy, industry holds the religious power, while church is a purely economic institution. I really like this temporal recursiveness of study over a territory: as the remnants of Roman Empire are studied thoroughly today, current Italian culture is examined in a hypothetical future under a similar archaeological lens. These concerns were already present in Thucydides (1.10.2): surviving material artifacts can lead to deep misreadings of history.

These fragments make me think inevitably about Leo’s project inside the MECANO network . While he is studying fragmentary texts of Ancient historians, he faces exactly these interpretive dangers - the temptation to fill gaps too confidently, to project present assumptions onto partial evidence. Yet his approach of studying relationships between ancient texts offers some protection against pure hermeneutic projection - and I believe it is the way to go.

When Classics Meet Corporate Publishing

Undisputedly, my favourite piece is “Regretfully, we are returning your…“. In this article, canonical works of world literature such as the Odyssey, the Divine Comedy or Don Quixote arrive to a contemporary publisher’s office and face editorial scrutiny, always leading to rejection of the manuscript. The piece consists of a collection of negative reader reports of these works. This way, the literary merit and timeless qualities that make these books classics are ironically “rejected” in favour of commercial appeal. My favourite puns were the ones about authorship and rights. See this excerpt of the reader report of the Odyssey (Eco 1994, pp. 35-36):

You can imagine that the Bible fares no better… as the editor’s name “doesn’t appear anywhere on the manuscript, not even in the table of contents. Is there some reason for keeping his identity a secret?”. The reviewer suggests keeping only the first five chapters: “we’re on sure ground there” (p. 34).

Playing with Seriousness

Eco’s playful scenarios illuminate something profound about Western cultural transmission. Canonisation - the process of deeming some works more important than others - shows a clear continuation since antiquity, as literary criticism is as old as literary creation itself. We can see the effects of canonisation everywhere, whether in ancient anthologies, or in the headquarters of Penguin Random House.

However, the mechanisms of canonisation were not stable all the time: while the economic value to be extracted from works in the book market has always affected canonisation and preservation (Johnson & Parker 2009), today’s process involves industrial production, mass marketing, and corporate consolidation.

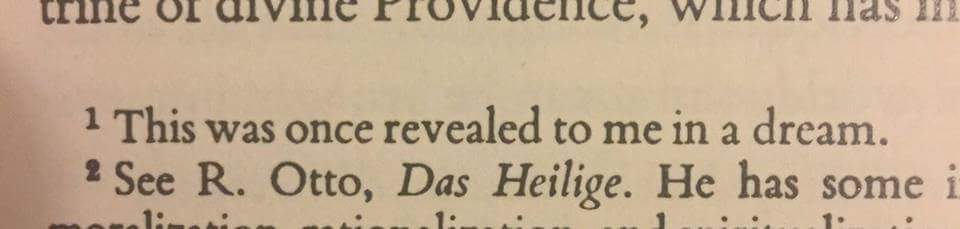

In general, I am struck by how canonisation reveals both continuities (the persistent practice of valuation) and discontinuities (the shift from scribal to industrial production) in Western cultural transmission since antiquity. The simplification of such complex knowledge transmission processes is very suggestive and funny. One example of this humouristic mechanism at play: the meme of “It was revealed to me in a dream” shows discontinuous standards for source credibility.

Figure 1: This footnote goes viral cyclically on social media.

Figure 2: Meme depicting the difficulties of being a historian in our times.

Simplifications, therefore, are a humouristic mechanism. But a funny simplification shows a good understanding of antiquity as well - or a good understanding of today’s view on antiquity. Even Umberto Eco simplifies the contemporary relationship between canon and market: the reality is that many canonical works are also best sellers in the publishing industry (Altick 1957; Porter 2018; Muñoz Rico et al. 2020).

As someone studying how ancient texts achieved their authoritative status, I find Eco’s humour very liberating. It reminds us that the canonical works we treat with reverence have a relationship with lightness and randomness. Recognising the contingent, sometimes absurd elements in cultural transmission doesn’t undermine serious scholarship. Instead, it might make our work more honest, more nuanced, and certainly more enjoyable. After all, if we can’t occasionally laugh at our own interpretive blind spots, we might just become the confused future scholars in Eco’s “Fragments” - so certain of our reconstructions that we miss what’s right in front of us.

References

- Altick, Richard D. 1957. The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800–1900. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Eco, Umberto. 1994. Misreadings. Translated from the Italian by William Weaver. London: Picador.

- Johnson, William A., and Holt N. Parker, eds. 2009. Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Greece and Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199793983.001.0001 .

- Muñoz Rico, María, Araceli García-Rodríguez, and José Antonio Cordón García. 2020. “Hacia una teoría del bestseller canónico: La constitución de un modelo estructural.” Revista General de Información y Documentación 30 (1): 149–165.

- Porter, J.D. 2018. «Popularity/Prestige». Pamphlets of the Stanford Literary Lab, no. 17 (September). https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet17.pdf .

- Thucydides. The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians. Translated by Jeremy Mynott. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.