Commentary, Canon, and Code: An Intern’s View on Ancient Philosophy

- Timo Zarakovitis

- Blog

- December 22, 2025

As summer came to an end, so did the first of the MECANO network’s so-called ‘non-academic’ secondments. For three months we (PhD candidates, Timo Zarakovitis and Kendall Bitner) left our usual posts at KU Leuven and Radboud University and took up shop at the Corpus Christianorum Bibliotheek & Kenniscentrum of Brepols Publishers, situated in the historic beguinage in Turnhout, Belgium. This miniseries highlights our experience there and summarizes some of our reflections and discussions on publishers’ continuing and evolving influence on processes of canonization.

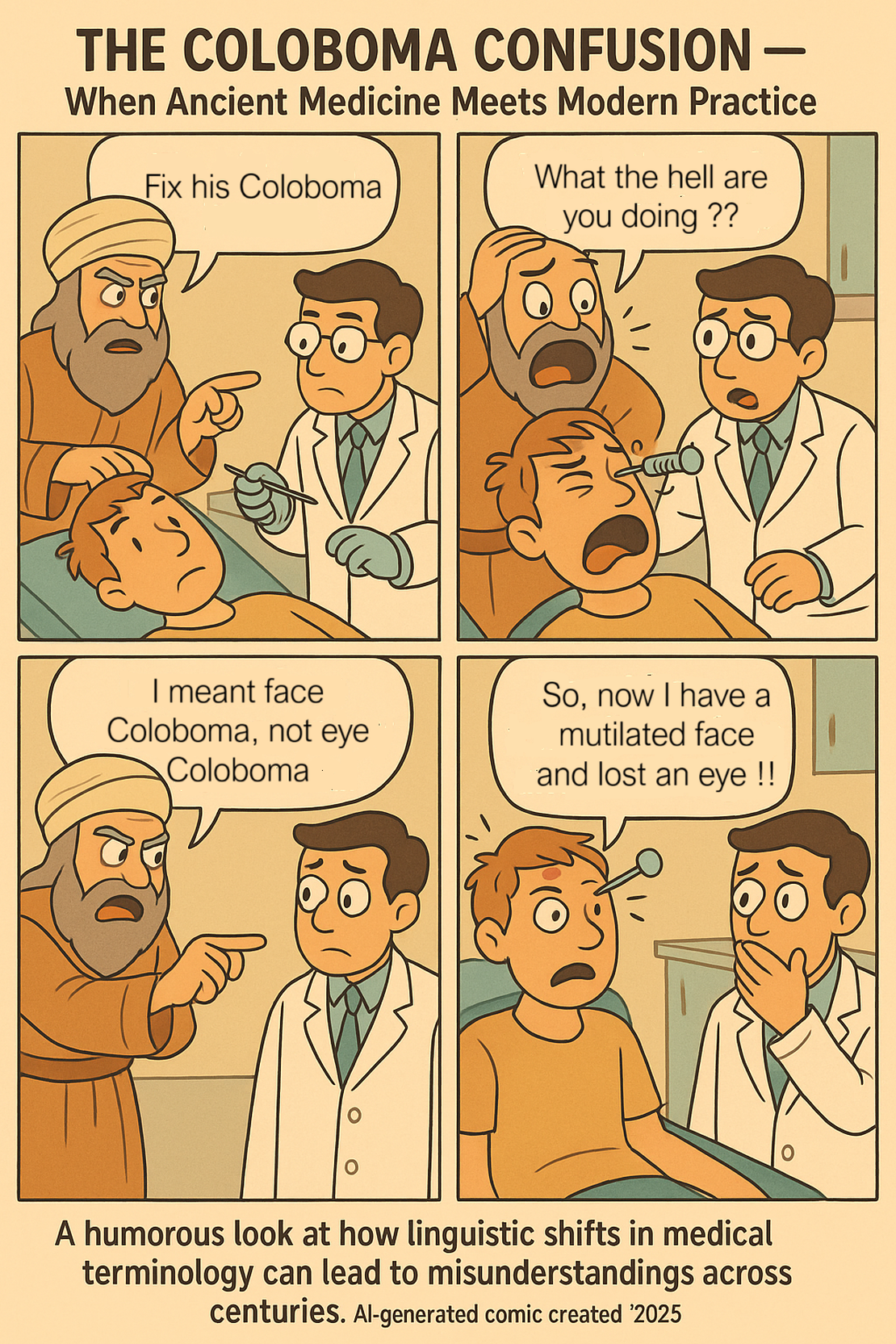

Ancient Authorities and the Question of Canon

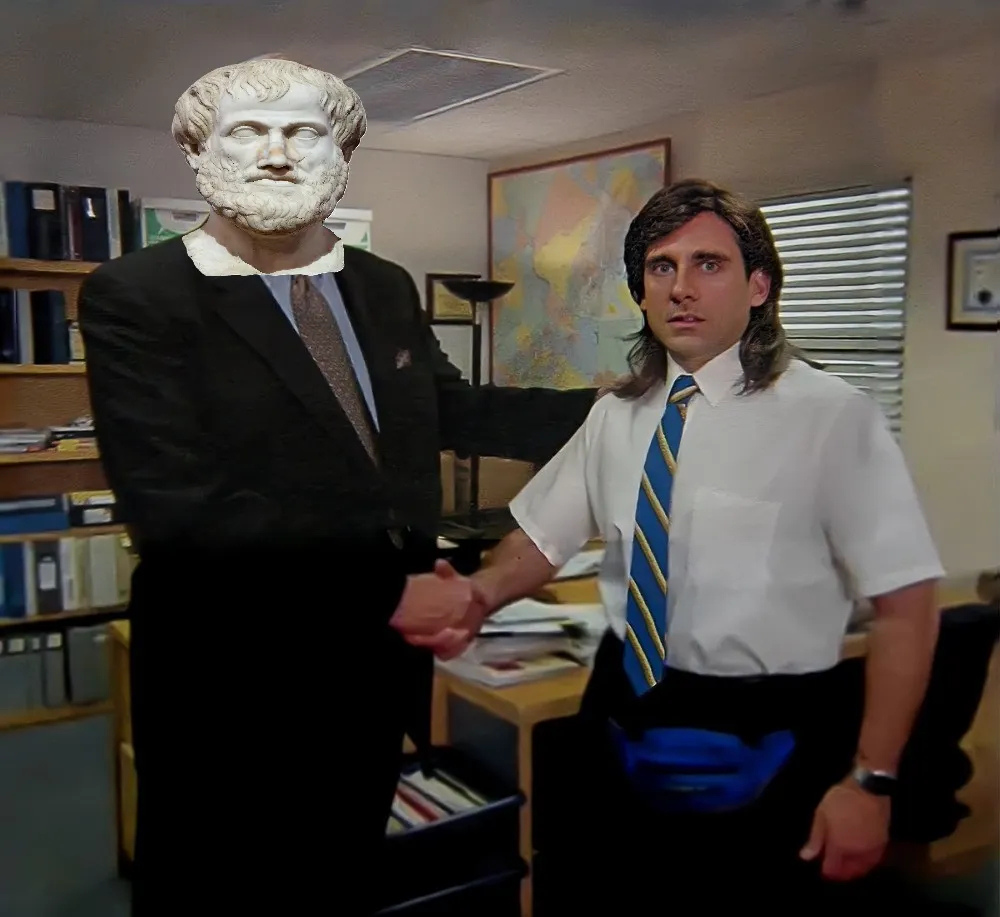

During my PhD, I’ve been reading Greek texts the old fashioned way, and also analysing them with some digital tools to find out how philosophers like Plato and Aristotle were quoted, commented on, and ultimately canonised by generations of scholars in a period which spans roughly a millennium. But this summer, I swapped my usual academic surroundings at the Kardinaal Mercierplein for something a bit different: an internship at Brepols Publishers and its Digital Classics lab, the CTLO, in the quaint beguinage in Turnhout, Belgium. During this secondment, I have been working on the Aristoteles Latinus Database, where I’ve had some unique opportunities to improve my digital skills, to see how a publishing house such as Brepols works, and how the canon continues to be shaped by (f)actors such as publishers with extensive series, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Canonisation is a difficult term, which might have a different meaning for every person. On a fundamental level, it refers to the process by which certain texts or authors are deemed “essential”, be it by being taught, copied, studied, or passed down through the centuries. But canons aren’t fixed and are always changing and evolving. What we consider classical or canonical today is the result of a long chain of decisions made by scribes, translators, scholars, and also publishers, which is why it was so interesting to see a different aspect of this tradition of canonisation. Some works survived because they were useful. Others, because they were simply fashionable at a given time. Some were even deliberately thrown out or ignored while others survived purely by chance.

Aristoteles Latinus and its Database

My internship at Brepols allowed me to approach these questions from a very different angle. The Aristoteles Latinus Database (ALD) is a digital resource containing Latin translations of Aristotle’s works and works about Aristotle, including commentaries and biographies. The ALD is a cooperative effort of Brepols and my colleagues of the Aristoteles Latinus Institute at KU Leuven. These Latin translations of Aristotle, mostly from the medieval period, were based on the original Greek texts and were crucial in bringing Aristotle’s ideas to Western Europe. Not all Latin translations of the Metaphysics, as my colleague and friend Nastas Jakšić informed me, were based directly on the Greek text. In fact, one very prominent translation, by Michael Scot (early 13th century), was made from Arabic into Latin.

During my internship, I worked on linking the Greek originals to the Latin translations by “XMLifying” their indices. The indices allowed me to trace how Greek or Latin lemmas (a form of a word that appears as an entry in a the abstract “common denominators” of the individual forms of a word) were rendered in the translation or original. These indices are extremely helpful for philologists and philosophers alike, as they explain the interpretation of these terms and of the entire philosophies. An inadequate translation or alternative understanding might completely change how Aristotle was to be interpreted for generations to come. Furthermore, this work of linking the Greek to the Latin may lay the groundwork for future projects, such as textual alignment or the creation of new digital tools for research.

One thing that really surprised me while working on the ALD during these three months was the sheer volume and diversity of Aristotelian texts that were translated, which was way more than I had initially thought. In my time as a philosopher, I had mainly focused on Ancient Greek philosophy, perhaps somewhat pushed by my background (or Canon!), but my time at Brepols really extended my view of this corpus. The fact that these translations were not just for the major (or canonical) texts, but also lesser-known or pseudonymous ones was also very surprising to me, as I had not expected that a work on, say, sleepwalking would be translated into Latin. All these things have really shown me how well regarded Aristotle was during this period, and one could thus argue that in those times, Aristotle was not just a philosopher, but indeed THE philosopher.

Translators as Canon-Makers

One of the most interesting aspects of my work on the indexes of the AL volumes was seeing how different translators interpreted things. Some, like the 13th-century William of Moerbeke, were extremely precise. He often provided not just a direct translation but also an explanation of the Greek term, especially when no exact Latin equivalent existed. There were also some anonymous translations, which I found out were less knowledgeable about the Greek. There were way more mistranslations to be found in their editions, and they often merely transliterated words they did not know or understand.

This, of course, is a big deal when translating a philosophical treatise where definitions play a key role. Whereas a good translation could help cement a text’s place in the intellectual canon, a poor translation might at best obscure its meaning or give wrong interpretations, or at worst could even reduce its influence. This really showed me that canonisation isn’t just about which texts are chosen and which are discarded, but also about how they are transmitted and by whom. If they are translated by someone who held a good reputation, this could ensure that the work would get taken up into the canon, while a poor translation of a major work could also potentially lead to its exclusion.

What Publishing Reveals about the Canon

At Brepols, next to working on the ALD, I also had a chance to observe editorial meetings and talk to publishing managers. It was extremely informative to see how decisions are made about which texts to publish, which databases to develop, and how to present them to scholars and libraries around the world, for which we were also asked our ideas and feedback.

It became clear to me once again that canonisation is still happening, although, with the shift towards the digital, sometimes in different forms. Decisions about funding, marketing, and even user interface design can influence what which texts get read, taught, and studied, and how. Long-running series like the Corpus Christianorum, which contains hundreds of texts, were referred to as “canons” by publishers. But even within these, scholars will have their own sense of what is truly central or less essential.

For me, this really drove the point home for me that the idea of a canon is never neutral, as it is shaped by scholarly interests, institutional priorities (as is the case for example with the AL and ALD), the demand of the market, and practical considerations.

Digital Humanities and the Expanding Canon

Working on the ALD also gave me (some more) hands-on experience with digital humanities, which I found both challenging and rewarding. I did feel that during these three months, my knowledge of Python, XML and databases has improved. Furthermore, some indices had over 4000 word pairs, and each editor had their own classification system, which could at times be frustrating, as I had to adapt my Python code for almost every file. Turning these into usable digital formats required not just technical skill but also a lot of patience and problem-solving capacities.

I do believe that the impact of this work could be significant. Online databases will reach new users and they allow for faster searching, easier cross-referencing, and entirely new kinds of research. They also help bring lesser-known texts into the spotlight, broadening our understanding of what the ancient canon was and what our canon of Antiquity or the Medieval times is nowadays. To summarize this then, digital tools do not just preserve our canons, they can even reshape them.

Reflections and Looking Ahead

One of the most rewarding parts of our secondment for me was feeling like being a true part of the Brepols’ CTLO team. We weren’t just observers or assistants, as we were often invited to give input, ask questions, provide ideas for future texts in the LLT (Library of Latin Texts) and help think about the future of the products Brepols offers. I also learned a great deal about the real-world applications of digital humanities, which are skills I will definitely take back into my PhD work. I believe this experience will help speed up the digitisation and preparation of my own corpus for analysis with digital tools such as text re-use detection.

To summarize my ideas about canonisation after our secondment: in theory, canonisation might seem like a slow, scholarly process, but in practice, it can be influenced by anything from market preferences to user experience. The canon is always evolving and expanding, and as more texts become digitally available and our grasp of the digital expands, this evolution is only going to accelerate.