How I Met MECANO: From Lexicon to Canon

- Doaa Elalfy

- Blog

- October 15, 2025

Growing up in a culturally rich, Arabic-speaking environment, the name Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) was familiar to me long before I encountered his writings. His al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb (القانون في الطب ), or The Canon of Medicine, was more than a historical text—it embodied a rich scientific heritage and a legacy of intellectual inquiry that had shaped generations.

During my academic research, however, I discovered something that shifted my perspective: the term Qānūn is not originally Arabic. Though today it is widely understood to mean “law,” Qānūn actually derives from the Greek word kanōn (κανών), meaning “measuring rod,” “standard,” or “rule.” In ancient Greek, kanōn referred to a carpenter’s tool used to ensure straight lines, an image that later developed into a metaphor denoting norms or standards in literature, art, religion, and science.

The term entered Arabic during the translation movement of the Islamic Golden Age, when vast bodies of Greek knowledge were rendered into Arabic. In this intellectual context, Qānūn came to signify a systematized, codified set of principles. Ibn Sīnā’s choice of this term for his encyclopedic medical treatise was intentional: it presented medicine as a standardized science, grounded in logic and universal principles.

This semantic journey, from kanōn to Qānūn, revealed the depth of intercultural exchange that has long shaped scientific discourse. It also underscored for me the importance of etymology and historical linguistics in understanding classical texts. A single word seemingly familiar could carry within it centuries of conceptual evolution, philosophical shifts, and cross-cultural dialogues.

As a native Arabic speaker, this realization felt like a tectonic shift beneath my linguistic feet. The semantic field I had always taken for granted was, in fact, layered with centuries of translation and transformation.

That insight ultimately led me to the MECANO project, whose research focus aligned perfectly with my interests. MECANO—The Mechanics of Canon Formation and the Transmission of Knowledge from Greco-Roman Antiquity—seeks to understand how texts, concepts, and authors became “canonical” through citation, translation, imitation, study, and compilation. It also investigates how these canons evolved when received in new cultural, linguistic, and intellectual contexts.

In MECANO, I found not only a research project but a framework for tracing the very kind of transmission I had encountered in Qānūn. The connection was immediate and profound, linking a personal linguistic discovery to a broader scholarly pursuit that bridges philology, history, and medicine.

To illustrate this process more clearly, consider the term coloboma. Derived from the Ancient Greek noun κολόβωμα (kolóbōma), meaning “a part taken away in mutilation,” it originates from the verb κολοβόω (kolobóō), “to mutilate” or “to dock.” Initially, it described general bodily defects or mutilations, but over time its usage became more specific within medical contexts. In modern medicine, coloboma refers to a congenital defect in ocular structures—such as the iris, retina, choroid, or optic nerve—resulting from incomplete closure of the embryonic fissure.

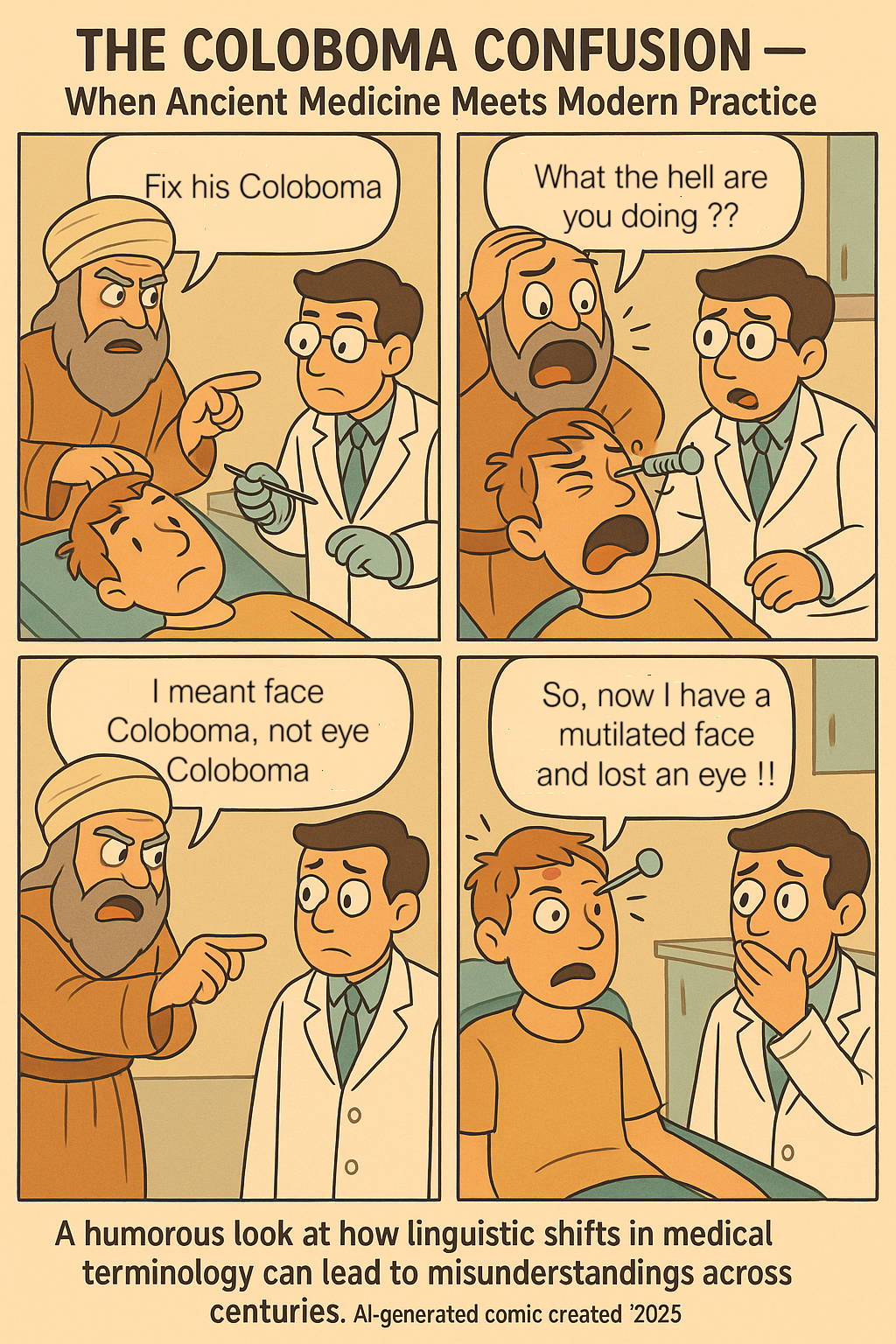

I first encountered the term coloboma in a short Greek medical papyrus at the beginning of my transition from the pharmaceutical field to the humanities. At that time, I quickly concluded that, alongside the term belonē (βελόνη, “surgical needle”), it referred to an eye surgery. Only later did I realize that, in its historical context, the passage actually described a facial procedure. I hadn’t misread the word but misunderstood it—unaware then of how profoundly semantic change could alter interpretation across time.

Image: AI-generated comic created by Doaa Elalfy, 2025. A humorous look at how linguistic shifts in medical terminology can lead to misunderstandings across centuries.

This narrowing of meaning exemplifies semantic change—the natural evolution of language in response to shifting cultural, scientific, and intellectual contexts. In medicine, such changes often reflect an increasing precision in terminology as knowledge expands. For scholars working with historical medical texts, recognizing these developments is not just helpful—it is essential. Interpreting a term like coloboma solely through its modern clinical definition, without considering its broader and earlier semantic range, risks distorting the intent and understanding of ancient medical authors.

Such transformations, however, are far from isolated. During my master’s research on Greek medical papyri, I encountered numerous terms whose meanings had shifted dramatically over time. A word that once signified a general ailment or bodily imperfection in classical Greek might reappear in Arabic or Latin sources with a refined—and sometimes radically different—connotation. Even within the same language, terms could acquire new nuances depending on the region, the period, or the medical tradition in which they were used.

These observations underscore a vital point: the historical semantics of medical terminology truly matter. Tracing the etymology and semantic trajectory of a term allows us to enter the intellectual world of ancient physicians with greater accuracy and empathy. It prevents anachronistic readings and opens the door to a more faithful reconstruction of past medical knowledge. For researchers in historical philology, history of science, or medical humanities, this kind of linguistic sensitivity is not merely a methodological choice—it is a scholarly imperative.

The dynamic evolution of language highlights why terminology is not static. Words like coloboma and kanōn do more than label medical realities—they actively participate in shaping them. Without a diachronic, contextual, and philological sensitivity, we risk misinterpreting historical medical texts, projecting modern meanings onto ancient terms, and overlooking the scholarly efforts of generations of practitioners and translators.

These semantic shifts are not mere academic curiosities; they are pivotal to interpreting ancient medical texts accurately. A misinterpretation of a term can lead to fundamental misunderstandings of remedies, theories, or diagnostic methods. In historical research, such errors can have profound implications. Recognizing the fluidity of language and the evolution of meanings is essential for precise analysis and comprehension.

This realization is precisely why I am now pursuing a PhD within the MECANO project. My research focuses on how lexical and structural shifts in medical terminology, from Greek to Arabic, reflect not only linguistic changes but also the intercultural transmission of pharmacological knowledge. I explore how these shifts influenced medical understanding across different eras and regions, shedding light on how knowledge was canonized, preserved, and transformed.

However, my path to MECANO was never planned. It began with a single word, whose meaning carried the weight of centuries, and a revelation that changed the way I saw language—as a living, changing genome, always affecting and being affected. That discovery led me to a project bridging philology, medicine, and cultural history—a journey that is still unfolding, one word at a time. That word became my doorway into a world where knowledge, practice, and culture converge, and through it, I discovered that even the smallest term can open vast landscapes of understanding. And this is only the beginning.